Arizona State University LEO-TIMS Camera Flight on Aurora Spaceplane, for University Space Research

Rockets dominate how we imagine space research and Earth observation. We tend to imagine iconic launches, long timelines, and missions where everything must work near-perfect first time. That model has produced extraordinary science, but it has also shaped how research is done: slowly, cautiously, and with very few chances to learn by doing.

A recent collaboration between Arizona State University (ASU) and Dawn Aerospace offered a glimpse of a different approach. Not a replacement for orbital missions, and not an attempt to shortcut rigor, but a complementary way to test real spaceflight hardware in conditions that are close enough to matter and forgiving enough to iterate.

ASU successfully flew a thermal-infrared camera aboard Dawn Aerospace’s Aurora spaceplane marking one of the first university-built camera to operate in near-space conditions aboard a reusable suborbital vehicle.

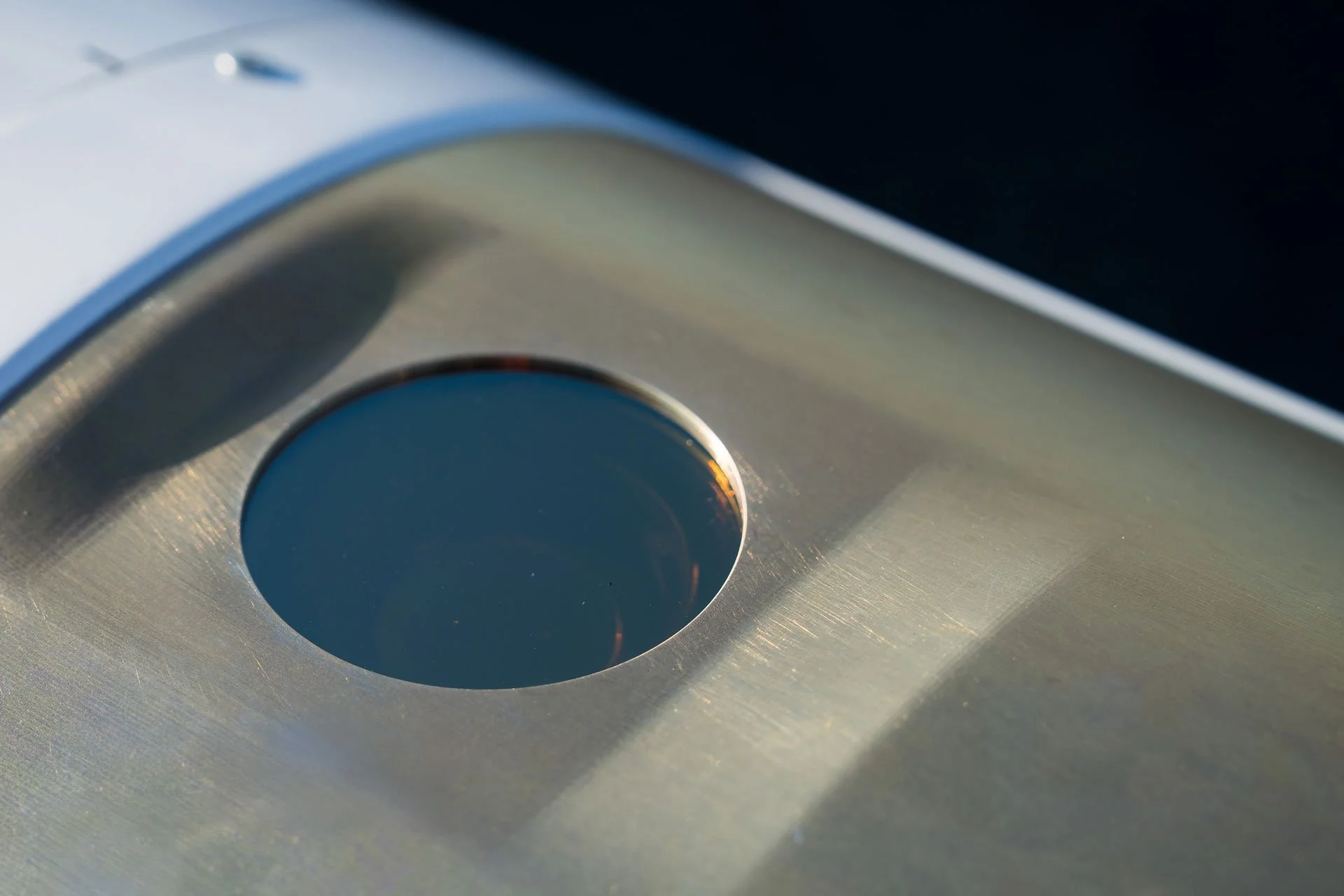

The payload, known as LEO-TIMS, is a compact thermal-infrared imager derived from heritage instruments that ASU has previously flown to Mars and soon to Europa, Jupiter’s icy moon, adjusted for LEO in a suborbital flight. Led by geologist, Professor Phil Christensen and mechanical engineer Ian Kubik, the mission sought to test how a scaled-down version of a planetary science camera performs in a fast, recoverable, and re-flyable environment.

Aurora | Pathfinder mission patch for the ASU LEO-TIMS payload flight. Image credit: Dawn Aerospace

“We’ve sent similar cameras to Mars and even to Europa,” said Christensen. “This project challenged us to take that same engineering and make it smaller, lighter, and dramatically cheaper so we could fly it on a spaceplane and collect real Earth data in months, not decades.”

For the ASU team, the timeline alone was revealing. From the start of the project to the first data was roughly four months. In planetary science, that kind of cadence is almost unheard of.

“Normally, a NASA mission takes ten years from idea to data,” Christensen said. “With Aurora, it was four months.”

During the flight, the camera recorded continuously, from before take-off through to landing. It captured infrared imagery of clouds, ocean, coastlines, and the curvature of the Earth. At one point, the instrument even imaged the Sun directly, a scenario the team had anticipated, modeled, and tested for extensively back at ASU. The camera came back intact, with no discernible degradation.

Infrared imagery from the flight revealed subtle temperature differences across clouds and water, offering clues for future Earth observation. “Infrared tells you temperature,” Christensen explained. “You can see which areas are wet or dry, where crops are stressed, or where ocean currents are shifting. These are vital insights for understanding how Earth’s systems work.”

Aurora’s onboard wing camera captures the aircraft in an inverted position, configured to enable an optical lens payload onboard to photograph Earth. Photo credit: Dawn Aerospace.

ASU LEO-TIMS optical lens image collection of Earth’s surface while onboard Dawn Aerospace’s Aurora suborbital spaceplane. Image credit: Arizona State University.

“As soon as it landed, I was already thinking about what we’d do differently next time,” Kubik said. “With quick turnaround, you immediately think to start designing the next experiment.”

Unlocking the Next Generation of Space Science

The ASU payload was not the only one flown. Dawn Aerospace also flew a commercial SDA camera for Scout Space on the same platform, and two other university payloads as part of its Pathfinder campaign, including California State University and Johns Hopkins APL.

The next-generation Aurora, capable of higher speeds over Mach 3.7 and higher altitudes of 100 kilometres (328,000 ft), is already in production, with test flights beginning late 2026. This vehicle is planned to operate from Oklahoma Spaceport, one of the few inland spaceports in the United States, located in Oklahoma, a state home to $44 billion in statewide annual economic activity.

Furthermore, this next-gen Aurora comes with a newly upgraded payload bay designed to support a broader range of experiments.

New Zealand and the United States together will form the backbone of future Aurora operations as the two flagship regions for the spaceplane program’s operational hubs.

A New Research Paradigm: Faster, Cheaper, Repeatable

For decades, space science has been shaped by scarcity: few launches, high stakes, and long delays between idea and outcome. Aurora introduces a different opportunity for suborbital payloads, and with it a different question: what would you build if you knew you could fly it again soon?

That question changes behaviour. It changes who gets to participate. And it changes how quickly good ideas turn into useful data.

For Dawn Aerospace, this collaboration reinforces Aurora’s role as a bridge between Earth space economies, enabling scientific testing, materials validation, and environmental research at a fraction of traditional cost and time. “That’s transformative for science and education” Christensen noted on reflection of flying with Aurora.

The short ASU payload film below offers a window into a different way of doing science, and a clear signal that Aurora is now available for both research and commercial payload flights.

For more information on payload and missions on the Aurora see www.dawnaerospace.com/spaceplane

Customer Interview Film:

Gallery:

Drone view of ASU optical lens payload onboard Dawn Aerospace’s Aurora suborbital spaceplane. Photo credit: Dawn Aerospace.

ASU LEO-TIMS optical lens payload onboard Dawn Aerospace’s Aurora suborbital spaceplane. Photo credit: Dawn Aerospace.

ASU LEO-TIMS optical lens image of clouds while onboard Dawn Aerospace’s Aurora suborbital spaceplane. Image credit: Arizona State University.

ASU LEO-TIMS optical lens image collection of clouds while onboard Dawn Aerospace’s Aurora suborbital spaceplane. Image credit: Arizona State University.

Dawn Aerospace staff and ASU lead engineer Ian Kubik with Aurora suborbital spaceplane on the afternoon following successful flight for the LEO-TIMS optical lens payload, 14th July 2025.

About Dawn Aerospace

Dawn Aerospace is a space transportation company developing the fastest and highest-flying aircraft ever to take off from a runway, alongside refuellable satellite propulsion.

Their spaceplane, Aurora — now available for purchase — combines the extreme performance of rocket propulsion with the reusability of conventional airplanes to enable high-frequency, low-cost access to suborbital space. Dawn’s propulsion systems are already operating on 42 satellites, and the next step is LOOP, an on-orbit refueling network, revolutionizing sustainability and scalability of in-space mobility.

Founded in 2017, Dawn Aerospace has over 130 staff across offices in the Netherlands, France, New Zealand, and the United States.

FOLLOW US

@dawnaerospace